Do the arguments in favor of a legalized trade in rhino horn stand up to basic scrutiny?

Let’s take a look at the nine most common myths perpetuated by rhino horn trade advocates.

Myth #1. “A legal trade in rhino horn is the ‘rhino poaching’ solution.”

In 1996, a total of six rhinos were killed illegally in South Africa, down from ten the prior year. At the Tenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to CITES in 1997, South Africa sought to expand its Southern white rhino trade from “international trade in live animals to appropriate and acceptable destinations and hunting trophies” to include rhinoceros “parts and derivatives”.

However — even at a time when illegal killing numbers were declining (the total was four in 1997, then one in 1998 and 1999) respectively — the Parties determined that South Africa lacked “adequate control mechanisms” for a legal trade.

Today, evidence suggests that South Africa’s “control mechanisms” have declined even further. Since 2003, unscrupulous members of South Africa’s private rhino community have been implicated in rhino horn trafficking. Even more troubling, is that very few of these game farmers, professional hunters and safari operators have been convicted. Pseudo-hunts continued unabated with the apparent knowledge of provincial authorities, while hundreds of rhino horns and trophies were exported to Vietnam and Laos with the approval of South Africa’s CITES authorities. Following negative international publicity about the Vietnamese pseudo-hunts and Julian Rademeyer’s ground-breaking book Killing for Profit, South African trafficking networks apparently attempted to use connections in the Czech Republic.

Mary Rice, Executive Director of Environmental Investigation Agency’s London office, explains that “commercial interests” are behind South Africa’s pro-trade rhino policies.

Powerful commercial interests in South Africa are seeking to cash in on their stockpiled horn at the expense of the conservation and survival of South Africa’s rhinos. Legalising rhino horn trade will reward the criminal kingpins behind the poaching, pushing rhinos inside and outside of South Africa ever closer to extinction.

It doesn’t matter if there is a “poaching crisis” or not: Rhino horn trade advocates have been pushing a self-serving agenda — not a solution — for decades.

Myth #2. “The trade ban has failed to save rhinos.”

Although international trade in rhino horn was banned in 1976, domestic trade in rhino horn was still allowed in China. Meanwhile, Yemen (the world’s largest importer of rhino horn in the 1970s) was not yet a member of CITES. So it seems that between 1976 and 1993, rhino horn trade was still “legal” in the two main markets for rhino horn. During this time, Africa’s black rhino population was decimated to a low of about 2,300 in 1993.

In 1993, the Chinese government finally removed rhino horn from the Chinese pharmacopeia, thus making domestic trade in rhino horn illegal. Yemen joined CITES in 1997 and a government-supported public awareness campaign helped close down its rhino horn market. By 2001, Esmond Martin and Lucy Vigne reported that “Rhino horn traders complained that the government ban on rhino horn imports had harshly affected their business”, and that educational materials on the plight of the rhino were disseminated in schools and public places in Sanaa.

“Among the pictures on these posters was a copy of the photograph of the religious edict or fatwa written by the grand mufti, which stated that killing rhinos was against the will of God.”

Since 1993, overall black and white rhino numbers on the African continent (and greater one-horned rhinos in India and Nepal) have increased — and continue to increase today, thanks to being protected from trade in rhino horn. The trade ban is more crucial than ever to the recovery of Asian rhino populations; this point is clearly stated in the Bandar Lampung Declaration, signed in October 2013 by senior government representatives from the Asian rhino range states (Bhutan, India, Indonesia, Nepal and Malaysia).

“The CITES ban in the international trade of all rhino products needs to maintained and enforced, including by those countries where rhino products are used, any countries that act as intermediate points in the trade, and all rhino range states.”

Myth #3. “A legal trade in farmed rhinos will save wild rhinos.”

Wildlife trade experts agree that commercial farming of tigers and bears have contributed nothing to the conservation of these species in the wild — and in fact, have hastened their demise.

Research published in February 2013 by the Environmental Investigation Agency revealed that at the time China began its so-called “conservation breeding” of tigers in 1986, the number of wild tigers in Asia was around 8,000. Today, there are a mere 3,200 tigers left in the wild, while the number of tigers held in China’s commercial breeding facilities has increased to at least 6,000.

“The Government of China allows legal domestic trade in the parts and products of captive-bred tigers, creating confusion among consumers, stimulating demand and driving the poaching of wild tigers and other Asian big cats.”

The Environmental Investigation Agency found that China has no clear system in place to distinguish captive-bred tiger skins from illegally sourced wild tiger skins, and that no information is available regarding how many tigers skins have been “registered and sold”.

Additionally, research such as Attitudes Toward Consumption and Conservation of Tigers in China, published in 2008, repeatedly indicates that consumers of wildlife products prefer what they perceive is the “real thing”, not farmed.

“[T]he clear preference for products from wild caught tigers shows that even if the demand for tiger products could be met from farmed tigers, a demand for wild caught tigers would remain. This is a critical point because the opening up of a legal trade would make it significantly more difficult to police the illegal trade as wild caught tigers and their products could be laundered through legal establishments.”

In a briefing prepared for the 2009 Global Tiger Workshop in Kathamandu, the wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC said that consumers in China and Vietnam prefer wild tiger products over those from captive-bred tigers, and that they continue to use tiger products, knowing it is illegal. The studies showed that consumers of tiger products are apparently “motivated by the belief that wild animals are ‘unpolluted’ and ‘precious’, as well as having nutritional and curative properties”.

Asia’s “bear farms” — supposedly a way to “sustainably harvest” bile from living bears — have proven to be a miserable failure for conserving wild bears. International trade in bear bile is prohibited, while domestic trade is still legal in China. Illegal bear bile facilities are operating throughout Southeast Asia, particularly Vietnam. Across Asia, approximately 12,000 bears live in “crush cages”, many with a tube permanently inserted into the gallbladder to drain the bile. A healthy bear’s life expectancy is 25 — 30 years, but the average life span of these bears is only five years. Since these bile-production facilities do not actually breed bears, wild bears are continually captured in order to replenish bile-producing stocks.

The industry’s surplus of farmed bear bile dispels the common belief that “flooding the market will save the species”: Dr. Chris Shepherd of TRAFFIC Southeast Asia explained via Mongabay.com that “the surplus of farm-produced bile has led to the use of bear bile in more products, thereby potentially generating more consumers and increasing demand.” Despite the abundance of farmed bear bile in China and other Asian markets, wild bears are still killed for their gallbladders throughout Asia and North America.

Commercial farming has not saved wild tigers or wild bears. There is no evidence to suggest this approach would protect wild rhinos.

Myth #4. “The rhino/vicuña comparison.”

This claim appears to be based on little more than “fiber and horn can both be harvested”, followed by “sustainable use” saved the vicuña from extinction while “alleviating poverty”. But does this comparison hold up to closer examination?

The pro-trade camp’s celebration of a supposed rhino horn and vicuña fibre parallel does not mention that the “poverty alleviation” hoped for in the vicuña model in reality “remains elusive” or that captive breeding (farming) of vicuña “fails to provide benefits for vicuña conservation”.

In 2010, Dr. Gabriela Lichtenstein, Chair of the South American Camelid Specialist Group (GECS), made the following points in the report Vicuña conservation and poverty alleviation? Andean communities and international fibre markets:

- The impact of the commercialization of vicuña fibre on the economic development of the Andean communities who are responsible for its management has proved to be very limited across the whole region;

- The large extent and promotion of the captive breeding programmes not only fail to provide benefits for vicuña conservation but are also threatening to lead (yet again) to the domestication of this wild species;

- Most of the benefits are captured not by local producers but by traders and international textile companies;

- The commitment for managing vicuñas in the wild under common property seems the best strategy for managing this common-pool resource.

Dr. Lichtenstein later warned in April 2012 that, “The economic value derived from the use of a wild species could be an opportunity for its conservation, but it could also pose an important threat.”

And vicuña shearing has not stopped illegal activities.

“Vicuña poaching is problematic in all four countries. The difficulty of controlling is related to the vast extent of the Puna, its topography and the existence of long international borders. Limited human, economic and technical resources make control ineffective.”

It is worth noting that trade in rhino horn raises certain ethical issues that trade in vicuña fiber does not: Rhino horn traders peddle their wares as a “cancer cure”, encouraging desperate people to consume rhino horn rather than seeking medical treatment for serious illnesses.

Myth #5. “The Chinese/Vietnamese/centuries-old tradition of using rhino horn will never change.”

History tells us a different story. Dr. Ron Orenstein, a zoologist, lawyer, and author of Ivory, Horn, and Blood: Behind the Elephant and Rhinoceros Poaching Crisis, speaks from 25 years of experience in this arena.

“A combination of strong and effective enforcement on the ground and effective regulation of the market, including demand reduction programs, has indeed worked in the past, and worked very well. During the 1990s, it was believed by many conservationists that rhinoceros conservation was on an upward trend as a result of such efforts in both Africa and Asia.”

Asian attitudes about wildlife consumption are changing: Southeast Asia and China are currently experiencing an unprecedented wave of public support for wildlife conservation. Recognizing the link between rhino horn use and rhino killings, the President of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine (ACTCM) and Council of Colleges of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine (CCAOM) released a statement in 2011 opposing the use of rhino horn in medicines.

Vietnam — identified as the primary destination for rhino horn from South Africa — has in fact joined the global community in several noteworthy demand reduction campaigns.

Education for Nature-Vietnam — a Vietnamese NGO — has released a powerful and innovative public service announcement which calls rhino horn users “ignorant, foolish, backward, cruel, and evil”. The video was launched during CITES CoP16 and ENV hopes the PSA “will help send a strong message to rhino horn consumers that this behavior is socially unacceptable, and the effects of this kind of consumption are being felt across the world”.

“Tiêu thụ sừng tê giác là hành động đáng lên án!” is the first in a new series of PSAs targeting rhino horn consumers to be released this year, and is part of ENV’s rapidly expanding rhino awareness campaign.

Humane Society International and the government of Vietnam launched a demand reduction campaign by distributing the book “I’m a Little Rhino,” to hundreds of Vietnamese children.

“Four hundred copies of the book were distributed to children at the mid-Autumn Festival organised by the Youth Union of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. Another 700 copies have been given to children at Viet Bun Kindergarten School in Hai Ba Trung district and children at Le Quy Don primary school in My Dinh district in Hanoi.”

Vietnam’s CITES Management Authority and HSI are planning a series of rhino-related events over the coming months.

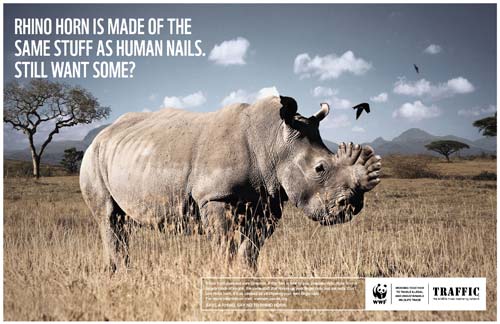

WWF and TRAFFIC joined forces with Ogilvy & Mather Vietnam to design an innovative visual campaign which aims to educate consumers that rhino horn is made up of keratin — the same as fingernails and toenails.

The adverts are being displayed in public areas and through many different communication channels, including newspapers, television, and social media platforms.

Myth #6. “Nothing is working/everything has been tried.”

Pseudo-hunts, stockpiling horns, exporting rhinos under questionable circumstances, and arrests of well-known members of South Africa’s wildlife industry suggest that perhaps the “solution” to South Africa’s rhino problem lies within its own borders.

Pro-trade advocates argue that South Africa has “tried everything”, yet high-profile rhino horn syndicate suspects Groenewald, Steyl, and Saaiman are still conducting business. Where are the meaningful prosecutions? Regarding the pseudo-hunts, where is the follow-up on the provincial players who authorized exports of rhino horns to Vietnam, again and again and again?

Mozambican “poachers” and Vietnamese couriers receive jail sentences for rhino crimes. In contrast, South African “game industry white guys” implicated in rhino crimes (charges often include money laundering and racketeering) receive postponements, pay paltry fines, and stay in business. Perhaps auditing the CITES documentation for rhino horn and trophy exports from South Africa from 2003 — 2012 would yield helpful clues regarding the South African safari hunt operators who supported these schemes.

“Corruption, collusion and sheer complacency are really the obstacles that stand in the way of effective enforcement,” says Dr. Chris Shepherd.

Ofir Drori, founder of Cameroon-based Last Great Apes Organization (LAGA) and author of The Last Great Ape: A Journey Through Africa and A Fight for the Heart of the Continent challenges claims made in September 2013 by IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group chairman Mike Knight that South Africa had done an “immense amount” to combat its rhino situation.

Drori candidly points out that, “No attempt has been taken to curb corruption and complicity of wildlife officials in the trafficking. Many traffickers go unpunished and are still ‘protected’, and the South African Government gives a lifeline to the criminal business other governments are trying to break by negotiating sales of rhino horns.” He urges South Africa to “start dismantling the organized criminal networks.”

At CITES CoP16 in Bangkok, I asked the South African delegation about encouraging its private rhino owners to join international efforts to reduce demand for rhino horn and support educational and public awareness campaigns in consumer countries. My question, unsurprisingly, went unanswered.

I also asked about the ethical implications of facilitating the sale of a bogus medicine to sick people. The answer indicates a disappointing lack of concern and responsibility. “As long as somebody believes it cures cancer, the demand should be met,” said Minister Molewa.

Until South Africa addresses the enforcement inconsistencies within its private wildlife sector, the claim that “everything has been tried” falls flat.

Myth #7. “The South African government banned domestic trade of rhino horn in 2009 and poaching increased after that.”

This willingness of the pro-trade camp to incriminate itself by admitting the facilitation of transnational criminal activity by supplying rhino horns destined for illegal markets in Southeast Asia and China is almost amusing.

Sadly, it suggests little, if any, sense of accountability regarding the global impact of “domestic” trade.

Myth #8. “Economics will save the rhino.”

As we learned in the bear bile example above, availability and affordability are unlikely to create market conditions favorable to protecting rhinos on a global scale. Rather, the abundance of affordable bear bile has created additional opportunities for bear bile facilities to expand operations by adding bile to shampoos, soaps and other non-traditional goods. The result? More bears captured from the wild in order to “produce” more bile — and a declining population of wild bears in Asia.

On the demand side, if “consumers will buy a good more frequently and in larger quantities as its price decreases”, then the availability of “affordable farmed rhino horn” may very well result in an increased demand for rhino horn — a disastrous outcome by any measure. There is further risk of increased demand if rhino horn consumption becomes “legal and unacceptable” instead of “illegal and unacceptable”.

Even if we cast ethical considerations aside (rhino horn has no proven medicinal properties!) for a moment, rhino horn stockpiles are finite — and so are the world’s rhinos.

Disturbingly, certain market players may already be “banking on extinction” by stockpiling wildlife parts, according to an economic study published in the Spring 2012 issue of the Oxford Review of Economic Policy . Legalizing rhino horn trade for one species, the authors argue, could create opportunities for laundering horns from other rhino species, noting that the extinction strategy is “particularly worrisome in cases where the extinct species is similar to surviving species” (the black and white rhino are used as an example).

While the authors of the report consider farmed rhinos as an alternative supply of horn — theoretically reducing pressure on wild rhinos — they also point out that owning a “renewable resource” makes the scarcity (and ultimate extinction) of the species in the wild even more desirable for farmers and speculators.

“Bear (or tiger) farming implies that speculators ‘own’ a renewable resource, rather than an exhaustible stockpile of a commodity such as rhino horn or ivory. This implies that they are able to enjoy monopoly rents for a longer, indeed potentially infinite, period, which enhances the profitability of banking on extinction.”

And speaking of stockpiles, South Africa has announced plans to seek approval to sell its government stockpile of rhino horns, seemingly oblivious to the deadly connection between the 2008 ivory stockpile sale, increased demand for ivory, and the current massacre of 30,000 African elephants annually.

But this insular decision comes as no surprise. During a press conference held at CITES CoP16, the South African delegation was questioned about the potential risk of trading in rhino horn, citing the example of the ivory sale and elephant killings. The response was simply that elephants were not being killed in South Africa.

Myth #9. “Emotion will not save the rhino.”

This statement is generally fired off as an insult to anyone who opposes the rhino horn trade. So, what motivates rangers and forest guards to protect wildlife? Hint: It isn’t a paycheck. “Emotion will not save the rhino” is a tremendous insult to the heroes who risk their lives every day on the front lines, motivated by hearts and minds — not wallets.

Let us consider that it is in fact emotion and its close relative — passion — that have propelled some of our most beloved leaders to change the world for the better.

Sources:

Environmental Investigation Agency (2013) Hidden in Plain Sight: China’s Clandestine Tiger Trade. London.

Gratwicke B, Mills J, Dutton A, Gabriel G, Long B, et al. (2008) Attitudes Toward Consumption and Conservation of Tigers in China. PLoS ONE 3(7): e2544. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002544

Foley, K.E., Stengel, C.J., and Shepherd, C. R. (2011). Pills, Powders Vials and Flakes: the bear bile trade in Asia. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia.

Charles F. Mason, Erwin H. Bulte, and Richard D. Horan. Banking on extinction: endangered species and speculation Oxf Rev Econ Policy (2012) 28(1): 180-192 doi:10.1093/oxrep/grs006

Lichtenstein, G. Vicuña conservation and poverty alleviation? Andean communities and international fibre markets. International Journal of the Commons, North America, 4, sep. 2009.

Lichtenstein, G. Vicuñas: Does population recovery mean a success for sustainable use? SULiNews: Issue 2 (August 2012)