In April of this year, yet another wildlife seizure was made in Hong Kong[i]. It involves a man allegedly smuggling ivory from (very appropriately) Ivory Coast, via the United Arab Emirates.

The media report does not indicate the person’s nationality or whether Hong Kong was to be the final destination.

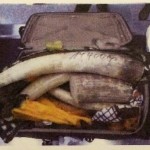

The article includes two photographs. One is a mixture of ivory products. It is not clear whether this is what was actually seized. The second was of more interest to me and I presume it is a true image of what Customs and Excise officials are said to have discovered. I find the photograph fascinating; for a number of reasons.

The image shows two items that might best be described as vests, waistcoats or gilets. Each has had many little pockets created on its inside. The pockets appear to contain a mixture of ‘raw’ and ‘semi-worked’ ivory. The semi-worked ivory seems to have been processed into small polished blocks, as opposed to having been carved into distinct objects, bangles or whatever. The raw ivory looks like the tips of elephant trunks and includes some very small and narrow tips. At least that is what the picture seems to show; it is not too clear. I’m no biologist or zoologist but that suggests to me that these came from juvenile elephants.

That’s troubling and may suggest that the poachers who harvested the ivory had been killing whole family groups. It might, alternatively or additionally, suggest that elephants are becoming so scarce in the country or countries where the poaching occurred that hunters are deliberately killing all ages, so desperate are they to acquire tusks, whatever the size.

That’s troubling and may suggest that the poachers who harvested the ivory had been killing whole family groups. It might, alternatively or additionally, suggest that elephants are becoming so scarce in the country or countries where the poaching occurred that hunters are deliberately killing all ages, so desperate are they to acquire tusks, whatever the size.

Those of us who have been involved in combating wildlife trafficking are well-aware of this type of vest being used by smugglers. In the past, however, it has tended to be favoured by couriers transporting eggs or small reptiles. It has perhaps been a less common concealment technique in relation to ivory-smuggling. Usually, because smugglers are conveying larger pieces of ivory; which would not fit into small pockets like those pictured here.

This is the third incident of this type, involving vests, which I know of occurring in Hong Kong in the recent past. Indeed, if memory serves me correctly, they all took place in 2016. I learned of all three via the media. Each, I believe, involved a mix of processed and unprocessed elephant ivory. Is this significant?

Of particular significance is that, in none of the cases I am aware of, were the couriers wearing the vests. Instead, the concealment clothing was packed inside their baggage.

In the latest incident, the vests apparently were in hand baggage, but I believe in at least one of the other discoveries, the vest had been within checked-in luggage. And that I find really fascinating. If those controlling these smuggling operations have gone to the trouble of creating vests with special pockets, and then supplying them to the ‘mules’, why are the couriers not wearing them? Or have they been instructed to only wear them if they encounter specific circumstances or don them for particular stages of the journey?

One hopes the smugglers are being questioned effectively, to find answers to some of the above questions and points. One hopes the waistcoats are being examined closely to discover clues as to how and where they are being made.

Each time contraband or a courier is intercepted, the law enforcement community is presented with a marvellous intelligence-gathering opportunity. Information can be gleaned and acquired which will help future risk-assessment, targeting and profiling; not only by the officials who made the detection but also by counterparts elsewhere in the world.

However, if those counterparts are to benefit, the intelligence and information needs to be shared with them. And that is where this media report really troubles me.

Regular readers will know that I recently praised officials in Hong Kong for their proud record of intercepting fauna and flora contraband. Sorry, ladies and gentlemen, but there’s to be no plaudits from me today.

You share intelligence among colleagues and counterparts. Your share it with agencies like CITES, INTERPOL and the World Customs Organization. You do not share it with the media.

And you don’t share it repeatedly with the media. If I have read the three media reports about the Hong Kong discoveries of smuggling vests being used by ivory couriers, I suspect those who recruited, supplied and paid them have read the articles too. If they haven’t, they don’t deserve to be part of an organized crime network and they’ll never earn the title of ‘kingpin’.

The stakes in the battle against wildlife trafficking are high. The law enforcement folks must emerge the winners. We know the opposition is sophisticated and organized. All too often, to employ a poker analogy, they seem to have been dealt better cards than ours.

It does not help if we show them what is in our hand.

[i] http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-crime/article/1936671/hong-kong-airport-ivory-bust-26kg-found-stashed-mans-vests