Despite the claims of trophy hunting advocates, there is scant evidence to show that the practice has benefited African wildlife conservation, according to new analysis published by the House Natural Resources Committee Democratic staff.

The comprehensive report, Missing The Mark: African trophy hunting fails to show consistent conservation benefits, revealed that the trophy hunting industry’s frequent claims that killing contributes to wildlife conservation are mostly unsubstantiated. In fact, “many troubling examples of funds either being diverted from their purpose or not being dedicated to conservation in the first place” were found during the assessment of trophy hunting revenue.

Trophy hunting has come under fire during recent years, perhaps most famously in July 2015 when American dentist Walter Palmer killed Cecil the lion in Zimbabwe under questionable circumstances. And since 2007, South Africa’s rhino poaching crisis has been facilitated by the country’s trophy hunting fraternity, which repeatedly used hunting permits to launder rhino horns for export to illegal markets.

“Claiming that trophy hunting benefits imperiled species is significantly easier than finding evidence to substantiate it.”

Four countries were assessed – Namibia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and South Africa – and researchers found serious gaps in the enforcement of wildlife conservation standards in all except Namibia. Wildlife mismanagement vis-à-vis trophy hunting has proven deadly for the African lion, African elephant, leopard, and both species of African rhino – particularly when combined with frequent U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service failures to demand relevant information before approving trophy hunting imports.

Corruption is, of course, at the heart of failed wildlife management policies in Tanzania and Zimbabwe.

In Tanzania, “corruption remains a serious problem, and is pervasive in all aspects of political and commercial life, but especially in the energy and natural resources sectors”. Although Zimbabwe has attempted to use trophy hunting as a conservation tool, “the government has been incapable of delivering the promised improvements in wildlife conservation or community development”.

And in South Africa, “serious concerns linger about the ability of government officials to manage wildlife populations”.

“While trophy hunting industry proponents assert that the presence of hunting operations deters poaching, there is no evidence of such an effect. Rhino poaching has soared during the last decade even as the South African government has encouraged trophy hunting.”

However, the United States also played a role in this disturbing cycle. The report revealed that although 2,700 “permit-eligible” trophies were imported from Namibia, Tanzania, Zimbabwe and/or South Africa into the United States during the period of 2010 – 2014, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued only *one* import permit.

Unfortunately, enhancement findings (determinations by USFWS that the importation of an endangered or threatened species will enhance the survival of the species) are “often based upon limited information” provided, in some instances, by parties with “potential conflicts of interest”. Well-funded hunting organizations (Safari Club International, for example) generate large amounts of unreviewed data proclaiming the benefits of trophy hunting. Without “the resources to generate it themselves or ground-truth it”, USFWS frequently relies on such data for enhancement findings.

“Some of these NGOs spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to generate data about the impact of trophy hunting on a species. At the same time, they may be spending significant resources to influence legislation and legislators while contributing to the campaigns of members of Congress directly.”

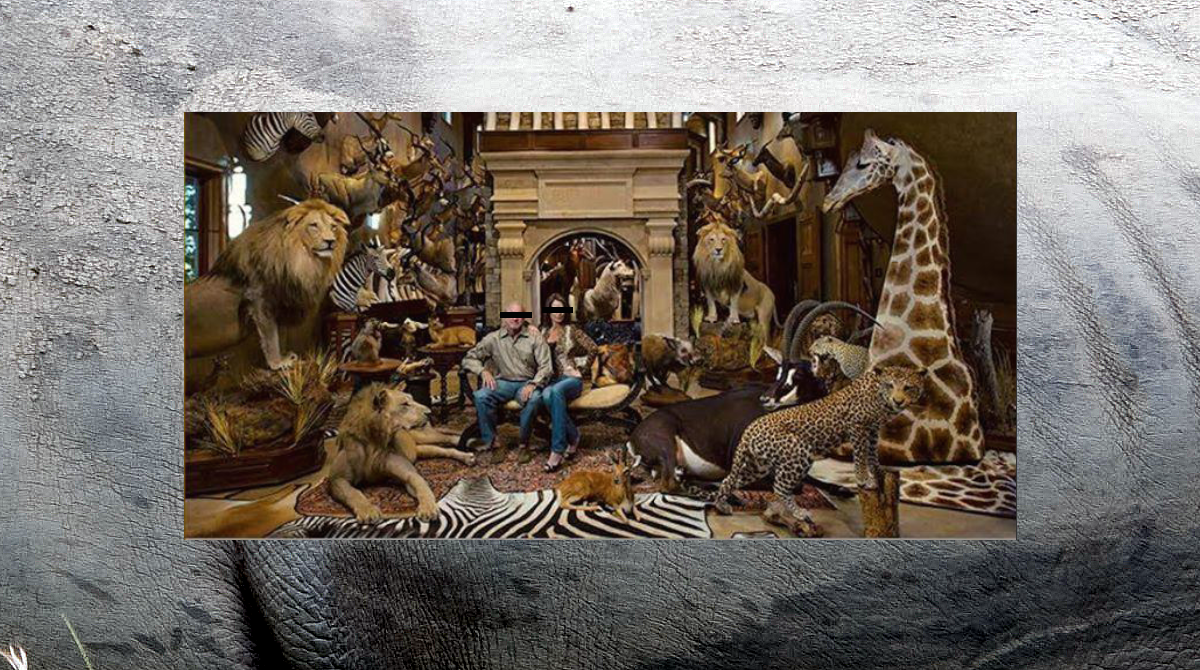

Trophy hunting in Africa is a privilege reserved for people who can afford round trip airfare to Africa, lodging, the services of guides and professional hunters, and other services. Indeed, the individuals applying for trophy import permits “do not fit the profile of the average American hunter”.

The report lays out multiple recommendations, including:

- Requiring more frequent and robust enhancement findings for ESA listed species;

- Closing loopholes that allow some trophies to be imported without a permit;

- Collecting additional data on trophy hunting through the permitting process;

- Increasing permit fees to fund science and conservation;

- Allowing only trophy imports taken using widely recognized best practices, including “fair chase”.

“While trophy hunting has benefited at-risk species in rare circumstances, most hunts cannot be considered good for a species’ survival,” said Committee Ranking Member Raúl M. Grijalva. “Taking that claim at face value is no longer a serious option. Anyone who wants to see these animals survive needs to look at the evidence in front of us and make some major behavior and policy changes.”

“Endangered and threatened species are not an inexhaustible resource to be killed whenever the mood strikes us.”

Well said, Mr. Grijalva.

Help fight against wildlife trafficking: Support our work to advocate for the protection of endangered species at the upcoming CITES CoP17 in South Africa.