On November 14, 2013 (rescheduled from October 8), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service plans to crush its stockpile of elephant ivory consisting of 5.4 tons of whole tusks and small carvings — items that have been seized or abandoned to the US government over the last 20 years.

This planned event marks the first time that the United States has moved to destroy its ivory stockpile, and only the second time that a nation outside of Africa has done so. As we count down towards this historic event, I recall the first time I became aware of the inherent difficulties in trying to destroy elephant ivory.

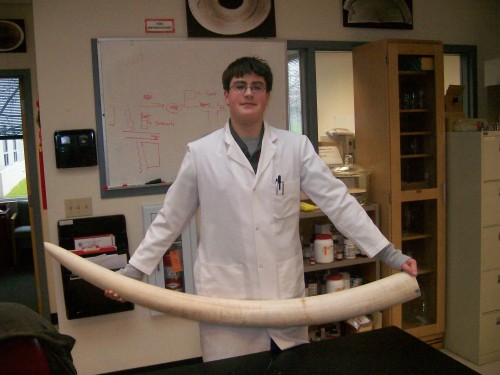

In March of 2008, my son Michael, then a junior in high school, completed an informal, week long internship at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Forensics Laboratory in Ashland, Oregon. Michael was contemplating a career as a scientist, particularly in the field of wildlife and environmental science. He had numerous discussions with teachers and advisors regarding the different types of work being done by scientists, i.e. field work, laboratory work etc. and we felt this would be an excellent opportunity to expose him to the work being done at a real laboratory by real scientists.

Upon arrival Michael was given a tour of the lab, and introduced to employees working in the different units. At the Morphology unit, Michael was shown how to identify ivory from different species using specific physical characteristics found in each. He was shown the distinctive cross-hatching, known as Schreger lines after the scientist who first described them, that is present in both elephant and mammoth ivory. The angle of the intersection of these lines, however, differs in elephants and mammoths and can be used to identify one form the other. He was also shown how to physically identify hippo ivory and walrus ivory from the shape of their cross section and the presence of secondary dentine respectively.

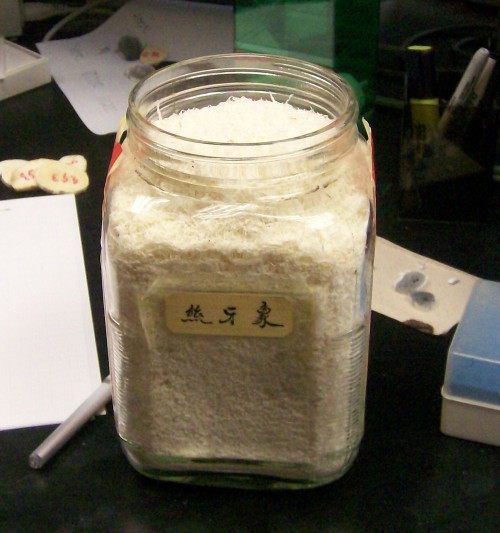

He was then asked to ponder the question, how would one go about identifying a sample of ivory that was devoid of any of these physical characteristics, such as is the case with a sample of ivory shavings (probably leftover residue from the carving process).

Under the direction and guidance of the laboratory’s Deputy Director, Dr. Edgard Espinoza, Michael designed and completed a laboratory experiment dealing with chemical analysis of different types of ivory, including elephant ivory. The purpose of the experiment was to determine whether the percentage of inorganic material that makes up the ivory of different species could be used as a means of identifying that ivory. Specifically, could the determination of the percentage of inorganic material in known samples of ivory from African and Asian elephants, walrus, hippopotamus, and mammoth be used to identify the species of an unknown sample of ivory shavings?

One interesting aspect of this experiment is that it involved the burning of ivory samples in a furnace at temperatures high enough to remove all organic material, a process known as pyrolysis. In fact, one of the first steps of Michael’s experiment was to determine the optimal temperature required to completely pryolize his samples. Through a series of trials, where he weighed each sample, using an analytical balance, prior to and after pyrolysis, Michael determined that the ideal temperature for his experiment was 1,000° Celsius for 15 minutes.

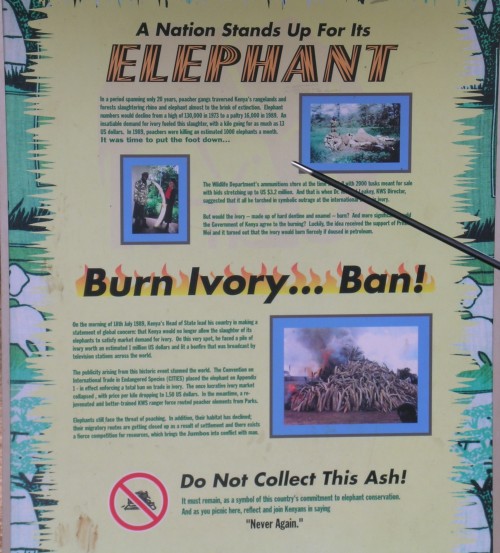

For me, this was an early indication of the difficulties of destroying ivory, especially large stockpiles of ivory. Up until that time, there had only been two historic ivory stockpile destructions, the first in Kenya in 1989 and the second in Zambia in 1992. Both of these destructions were carried out by the hugely symbolic method of creating a large pyre of stacked ivory tusks and dried wood and ceremoniously lighting it on fire. In 2006, I had the good fortune to visit the memorial to the first destruction event, located at the burn site in Nairobi National Park in Kenya. It consists of a large stone ring containing the ash and remnants of the burn and a memorial plaque dedicated to the occasion. Among the ash and remnants there isn’t anything that even so much as resembles an ivory chip. It hadn’t occurred to me at the time how long and hot the fire had to have been to completely render those huge tusks down to a pile of ash.

Since that time, Kenya has conducted a second burning in 2011, as did another African country, Gabon, in 2012. We have also seen the historic event of a non-range country, the Philippines, destroy its ivory stockpile in June 2013, marking the first time the destruction of a country’s ivory stockpile was done by crushing instead of burning.

According to the fact sheet published by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the US will destroy its ivory stockpile using an industrial grade rock crusher. The fact sheet recognizes the difficulties of trying to destroy large amounts of ivory by burning and also mentions the significant amount of air pollution that would be created by doing so. It is unclear down to what size the ivory will be crushed, but it is clear the intent is to remove any possible commercial value to what is left of the ivory. The fact sheet also indicates that a final decision has not been made as to what will be done with the remaining material. Hopefully creative minds can come up with an educational use that will further the message that elephants poaching and ivory trafficking need to stop.

By the way, the results of Michael’s experiment indicated that the ivory shavings had a close inorganic percentage with the African and Asian elephant samples, but was most closely related to the mammoth ivory sample. This was rather unexpected given the sample of ivory shavings appeared pristine and very white and not what you would expect as coming from an animal that has been extinct for at least 10,000 years. To confirm this unexpected result, Dr. Espinoza had Michael analyze the pyrolized ivory samples using an x-ray fluorescent spectrometer to determine the percentage of elements in each. He found that the unknown ivory sample had much higher levels of Strontium than the African or Asian elephants and was consistent with the Strontium levels found in the mammoth sample, thereby confirming that the unknown ivory sample was actually made up of mammoth ivory shavings.

I recently asked Michael what were the most memorable parts of his internship at the forensics lab. He responded that he remembers being treated like an adult and that “after I was taught how to use the [laboratory] equipment, they let me work the experiment pretty much independently.” He also recalls that “it was pretty neat for a high school kid to be able to handle and work with exotic species like elephants, walrus and hippo” and that he remembers “being able to hold a really big, really heavy elephant tusk.”

When I told him that elephants with tusks that big are rare in the wild in Africa (by some accounts there are less than 40 big tuskers left in the wild) and that they have been culled from the population over the years by poachers who target elephants with the biggest tusks, Mike responded, “well, that just makes me sad.”

Yes, Mike, that’s exactly right.