International concern is growing around South African game industry insiders who are dabbling in illicit rhino horn and lion bone trade.

With fewer than 4,000 wild tigers left — some estimates place the wild population at a mere 3,200 — a sharp increase in the lion bone trade strongly suggests that lion bones are being substituted for tiger bones in the Chinese medicine market. (Tiger bones are used as a “health tonic” in traditional Chinese medicine, and like rhino horns, have no proven medicinal value.)

Similarities to rhino horn trade

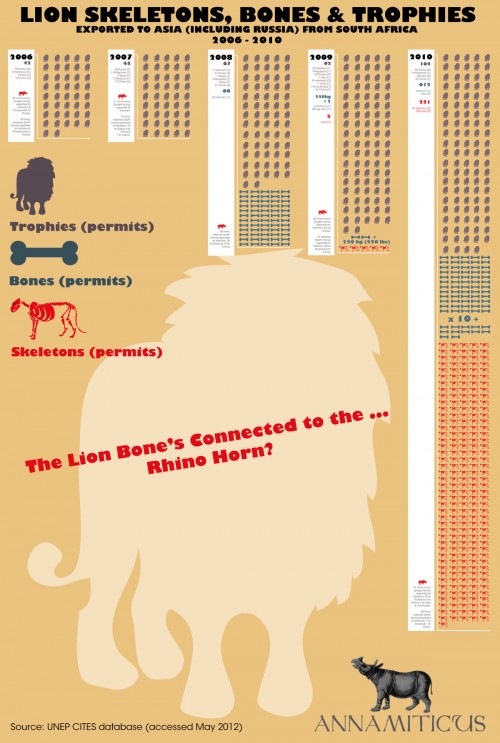

Trade records indicate that lion trophy and bone exports, along with rhino trophy and horn exports from South Africa to Asia (including Russia) both increased significantly between 2006 and 2010. (Note: South Africa’s white rhino population and lions are listed under CITES Appendix II, which means some trade is permitted.)

In 2006, a total of 42 lion trophies were exported to Russia (23), Indonesia (2), India (2) and China (15), while 18 single rhino horns and 40 rhino trophies (both horns) were exported to Vietnam and 10 single horns and 20 rhino trophies were exported to Russia. There were no lion bone exports recorded until 2008, when 60 were exported to Vietnam under one permit.

By 2010, a disturbing pattern had emerged. 104 lion trophies were exported to Russia (33), the Philippines (1), Laos (54) and China (16); 612 lion bones were exported to Vietnam and Laos (distribution was unclear); and 221 lion skeletons were exported to Vietnam (91) and Laos (130). The same year, trade records show that 91 single rhino horns and 20 rhino trophies were exported to Vietnam, six horns and one trophy to China, four single horns and seven trophies to Russia, ten single horns to Thailand, and four to Laos.

In a March 2012 Behind the Schemes podcast, Dr. Kat of the UK-based charity Lion Aid explains that the lion bone market is a “spin-off” business from trophy hunting.

“It’s a spin-off from this trophy hunting market, because the trophy hunter only wants the skin and the head and things like that, and they don’t necessarily want the bones. So what has been happening more and more, since the farmers and the ranchers and the breeders realize that these bones now have value, they’re being exported to various countries in Asia.”

And — just like the rhino horn situation — it seems the greed in South Africa’s private sector has contributed to the issue.

“This is one of the things that has happened with allowing wildlife into private hands. The private owners obviously want to make the maximum profit they can. And so therefore, they can sell the lion twice, once for its trophy value and again for its bones.”

For example, South African safari operator Marnus Steyl was arrested in 2011, along with Thai national Chumlong Lemtongthai, for allegedly laundering rhino horns (using bogus trophy hunts) for the illegal market.

A 2011 Media24 investigation by journalist Julian Rademeyer revealed a paper trail of business transactions and photographs which established that in addition to rhino horns, Steyl was supplying lion bones to Lemtongthai’s employer, Xaysavang Export Import, based in Laos. (Editor’s note 08/31/2013: Julian Rademeyer’s book Killing for Profit, published in 2012, exposes the Steyl-Lemtongthai case in detail.)

The paper trail also led to another associate of Steyl and Lemtongthai — Punpitak Chunchom — who had already pleaded guilty to illegal possession of lion bones and was expelled from South Africa.

However, Steyl wasn’t the only game industry insider to be fingered in the illegal rhino horn trade.

Lion breeder nabbed for rhino crimes

Clayton Fletcher of Sandhurst Safaris was nabbed in 2006 for his alleged involvement with a rhino horn syndicate (dubbed the “Boere Mafia”).

Four years after several suspects were arrested in connection with the “Boere Mafia”, the long-awaited trial was swiftly struck from the roll — much to the dismay of international onlookers.

It is interesting to note that at the time of his arrest, Fletcher was running one of the largest lion breeding operations in South Africa, and he has also been a key player fighting for the lion breeding industry amidst the long-standing controversy over “canned lion hunting”. In 2007, a Cape Argus article explained that the Fletchers were breeding two to three times more lions each year than were being hunted on their property, and News24 reported that about 280 lions were located at Sandhurst Safaris.

Is it possible that Fletcher’s (alleged) rhino horn customers were also purchasing lion bones (like suspects Steyl and Lemtongthai)?

‘Creating a new market’ for lion bones

In 2010, David Newton of the wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC was quoted in IOL, regarding the existing trade in lion bones from within the private game industry.

Newton said that a “limited trade in lion bones” was occurring, and added that captive lion breeders could exploit the situation and “create a new market”.

“I’m not sure the captive-lion breeders help conservation. To some extent they are creating a new market, so TRAFFIC does not support tiger farming or lion farming where the final product is bone. We think there is a risk that some animals will be mixed up to create a new market.”

Apparently, “alarm bells rang” when a permit containing “English and Chinese text” was issued in the Free State province to export lion bones to a neighboring province, suggesting that some lion breeders already had established connections with the end user market.

Co-authored with Sarah Pappin.

3 thoughts on “The Lion Bone’s Connected to the … Rhino Horn?”

Comments are closed.