By Douglas Hendrie, Crime Unit Advisor, Education for Nature-Vietnam

The case file reads like a book: Nearly 25 pages of documentation detailing Education for Nature-Vietnam’s efforts to take down a wildlife trader who is referred to internally within ENV as the “Bastard of the Internet”.

The story starts on August 16, 2013 when ENV received a call on our Wildlife Crime Hotline from a member of the public reporting a macaque advertised for sale on the internet. A phone number leads us to a shop in Tan Binh district of Ho Chi Minh City where an assortment of wildlife including macaques and ferret badgers are observed. However, it was four days later before police inspected the shop and of course, the wildlife had disappeared.

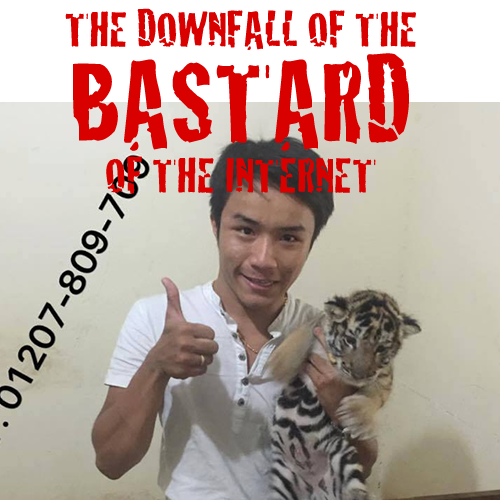

This incident started what would become more than a two-year campaign to shut down Phan Huynh Anh Khoa, AKA the Bastard of the Internet.

Khoa deservedly earned his name over the course of our investigation campaign by advertising a wide assortment of endangered and protected species including douc langurs, leopard cats, pangolins, marine turtles, otters, and lorises on his personal Facebook account and on websites and forums. His evolving list of live animals for sale goes on and on, reading like the inventory of a small zoo, and includes both native and exotic wildlife.

During our investigations, we actively sought his arrest and worked with police to organize more than 25 inspections of his shop, where he openly sold wildlife. However, only a handful of squirrels and exotic chickens were confiscated. Moreover, Khoa mocked authorities and ENV on his Facebook account, promising that he would never be caught and cursing ENV at every turn.

Khoa’s boldness was perhaps derived from the support he is suspected of getting from people in the local government.

These individuals may have tipped him off about upcoming raids, allowing him to stay one step in front of any successful enforcement effort. In one case, he gloated about receiving a correspondence that ENV had sent to local government only a day or two prior, which seemed to confirm that he was getting help from above.

Khoa frequently talked about traveling to Thailand and Cambodia to buy animals. ENV took to profiling Khoa, reviewing his electric bills, bank account information, and interviewing friends and relatives in order to obtain some vitals such as his passport number, all so that ENV could widen the net and potentially get Khoa when he crossed international borders.

After learning of his travels, ENV began regularly alerting authorities in Thailand through our partner, Freeland Foundation, in addition to the Wildlife Alliance in Cambodia, which operates a wildlife crime enforcement team. At one point, one of Khoa’s traveling companions was caught in Cambodia smuggling wildlife during his return. In another case, Khoa complained that during one of his buying missions he was checked by Cambodian border police, suggesting that efforts through the Wildlife Alliance might pay off in time. However, despite all these efforts, Khoa still managed to elude capture.

It was not until late 2015 when an investigation, for which details cannot be discussed at this time, opened the door of opportunity for ENV. On December 2, Khoa posted a photo of a baby langur that he wished to sell. ENV’s undercover investigator, having already established a relationship earlier with Khoa posing as a buyer, made contact and expressed interest in purchasing the langur as well as 10 otters that Khoa told our investigator he had for sale.

ENV contacted the National Environmental Police in Ho Chi Minh City and set the trap in motion. The objective of this “sting operation”, similar to many other sting operations that ENV routinely carries out, was to get Khoa, the animals, and police to the same spot, during which the police would make an arrest.

This was no easy task: Khoa had to be kept on the line while our undercover investigator convinced police to act immediately, something they rarely do.

Adding complications to the ordeal, on December 3, Khoa called our undercover investigator and reported that the langur had died. Our investigator instructed Khoa that she would still buy it, and to just put it in the refrigerator to preserve it. The deal is happening, but pressure mounts for quick action as Khoa tells us that he is going to Thailand. The deal has to happen today.

Our investigator immediately provided Khoa’s bank account information to police who then made an initial deposit to move the deal forward. What follows is a flurry of phone calls between the investigator and police, and further calls to Khoa to set up the buy. All was arranged. Well, almost.

An undercover officer named B was tasked with making contact with Khoa on behalf of ENV, but Police were concerned with how to get B out of the way after the initial meeting so that police could make the arrest without implicating him. B was an inexperienced, dare I say, incompetent, front man, tasked with a difficult and potentially dangerous undercover mission. Our investigator schooled the officer on techniques used to disengage just before a raid, but Khoa is not your average trader. His ability to smell a trap and elude capture has been remarkable over the previous two years. B’s inexperience was of great concern and our investigator feared that B would blow the deal. There was also some concern over the safety of B given his inexperience.

Our undercover investigator asked for a photo of B so that we could describe him to Khoa as the pick-up guy, and was alarmed when the photo arrived showing a boyish young man, hardly suitable for the role he was playing. But it was too late. The wheels were in motion. The enforcement team was poised to make the arrest and B was their man.

It is now 5:30 PM when the phone rings. Khoa is irate. He questioned whether B indeed worked for our undercover investigator, who was posing as the buyer. “He is a fool and he knows nothing about wildlife at all,” said Khoa. Our investigator sensed the deal slipping away and quickly told Khoa that she did not like B either and that following this deal, she would probably fire him. She further agreed that he was incompetent and that he was a problem for her outfit, and asked Khoa to let her know how he does so she can get rid of him after the deal. Khoa settled down and reluctantly agreed to make the deal.

As police closed in, more phone calls were made to Khoa aimed at getting him to bring both the langur, which was at his house, and the otters, which were at his shop. We wanted him to bring these animals to a public location where he could be arrested while transporting the wildlife, which is a more serious charge.

At 6:27 pm, police alert our investigator that Khoa has been arrested outside of his shop in possession of nine otters, a dead black-shanked douc langur, five lizards, a crocodile, and some squirrels.

The outcome marked the end of a long battle to take down the “Bastard of the Internet”. However, the battle is not really over until the Khoa is tried in court and punishment is applied. The question remains, is Khoa going to come out of this a changed man? Or is he going to go back to the life he knows well, more cautious than ever, and continue his lucrative business selling endangered wildlife?

This case succeeded because of the hard work and efforts of many ENV case officers over the past two years, but especially as a result of the dedication and commitment of our lead investigator. Had it not been for her drive and exceptional coordination skills in dealing with both Khoa and the police, this case would not have ended with an arrest. ENV is not a government agency, nor are we tasked with enforcement, and yet lack of an effective response by law enforcement leaves us with few to depend upon other than ourselves. We can only hope that our efforts will lead to steadily improving capacity as front line police officers are exposed to the likes of our highly motivated investigators, perhaps seeing a future Vietnam in our people that they can aspire to.

![The UN’s Lone Ranger: Combating International Wildlife Crime [Podcast]](https://annamiticus.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/BehindTheSchemesEpisode37-500px-150x150.png)