Is there money to be made from selling fake rhino horns to poachers? Would a line of consumer products containing “essence of rhino horn” turn a profit? The founders of Pembient, a San Francisco-based biotech company, hope the answer is “yes” to both questions.

Pembient can reportedly produce synthetic rhino horns that “pass as the real thing” using the “latest techniques in biotechnology” and the company says it plans to reduce the illegal trade by releasing its horns into the market, according to Reuters.

“In order to attack the price of rhino horn, we’ve decided to fabricate them in a lab,” say Pembient founders Matthew Markus and George Bonaci, who have backgrounds in genetics and biochemistry. “By creating an unlimited supply of horns at one-eighth of the current market price, there should be far less incentive for poachers to risk their lives or government officials to accept bribes.”

Markus told the Puget Sound Business Journal that he was “always interested in merging biology and computer science, but wasn’t interested in the long, arduous process of bringing a drug to market”, thus allowing Pembient to avoid regulation by “agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration”.

Pembient’s profitability depends on a continuing demand for rhino horn in the two major rhino horn consumer countries: China and Vietnam. In China, Pembient is partnering with a Beijing brewery to produce a rhino horn beer, which the company hopes will be released in late 2015.

After spending “more than a month” in Vietnam, Markus hopes Pembient can capitalize on the country’s demand for rhino horn with “essence of rhino horn” consumer goods, as shown in the video below:

The Pembient concoction will be sold as “horns” and powder. “This market likes powders, pieces, and whole horns,” Markus was quoted as saying in a Fast Company interview.

“Just like Silicon Valley people like laptops, cell phones, and tablets … it’s basically different forms and we have an answer for each form.”

Pembient tells Quartz it “doesn’t intend to sell the raw material directly to consumers”, but rather use synthetic rhino horn to “manufacture consumer products such as lotions, beverages and traditional medicines.”

Pembient also believes poachers could be its “best customers”. In an online forum, one of the co-founders mused, “I suppose you could [3D] print horns and leave them lying around for poachers to sell.”

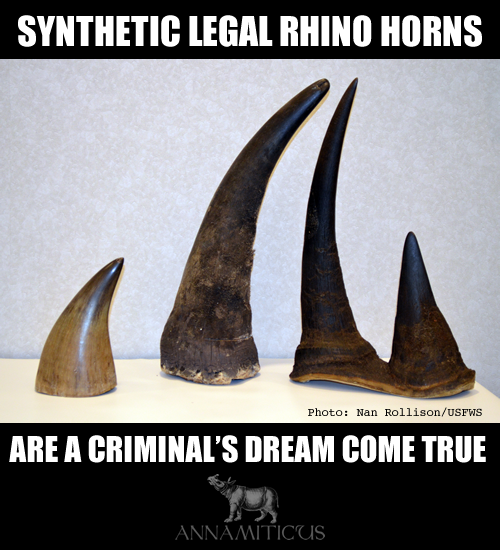

Pembient admits it “can’t really control what happens to our horns once they leave our distribution points”. This, of course, means there is no mechanism to stop synthetic horns from being traded as real horns in the black market — especially since one of Pembient’s goals is to make it “more costly” to test for differences between its product and real rhino horn.

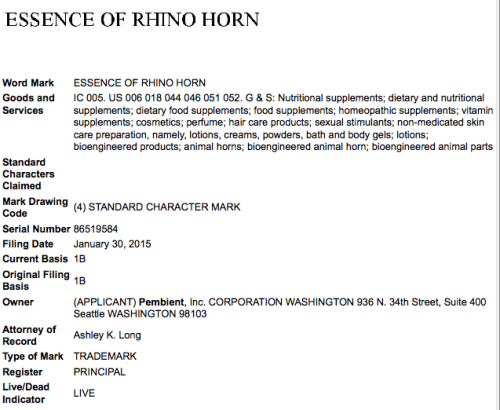

Pembient might expand its earnings potential with the inclusion of a wide array of uses for rhino horn, such as those listed in the company’s trademark application for “essence of rhino horn”: “Nutritional supplements; dietary and nutritional supplements; dietary food supplements; food supplements; homeopathic supplements; vitamin supplements; cosmetics; perfume; hair care products; sexual stimulants; non-medicated skin care preparation, namely, lotions, creams, powders, bath and body gels; lotions; bioengineered products; animal horns; bioengineered animal horn; bioengineered animal parts”.

Pembient’s ambitions go far beyond profiting from rhino horn, stating that its “mission” is to “replace the $20 billion illegal wildlife trade with sustainable commerce”. The company has raised at least $100,000 in private equity as of January 30, 2015, according to its Form D filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Will Pembient’s synthetic rhino horn distribution plan benefit the species — or will it keep the bloody rhino horn business rolling?

Pembient says it would sell its product at “one-eighth the current market price”. The common headline figure of $60,000 per kilogram (“more expensive than gold or cocaine!”) is quoted. Pembient fancies the idea of selling its product to “poachers”, but fails to address other black market operatives. A rhino horn, once separated from its rightful owner, will change hands — and prices — many times.

The former head of CITES enforcement, John Sellar, OBE, writes that the price of wildlife contraband depends on what country and “consequently, at what point in the chain of criminality”.1

“An elephant tusk handed to a dealer or poaching organizer in the country where the animal was killed, for example, gives a much smaller return than it does when, perhaps many months later, it is delivered into the hands of a trader in Asia.”

The National Wildlife Crime Reaction Unit (NWCRU) in South Africa explains that there are five key levels in its illegal rhino horn market.2

- Level 1: Individuals and ad hoc gangs who poach rhinos, expendable “foot soldiers” who earn the least in terms of the value of the rhino horn.

- Level 2: Gangs consisting of trackers and shooters; the subset of more sophisticated players from within game ranching communities, including criminalized professional hunters, veterinarians and other game industry operators, who generally target rhino on other private sector properties. These groups may also simultaneously function as low ranking buyers or local couriers obtaining horns from illegal private sector activities, including dehornings.

- Level 3: Middlemen buyers, exporters and couriers who are typically nationals of the African countries they operate in, and work through local and regional networks that procure horns through various channels.

- Level 4: Operatives who are responsible for illegally exporting rhino horns out of Africa to Asian destinations. The dealers at this level are most often African-based Asian nationals with permanent or long-term resident status within key countries such as South Africa. They typically are linked to networks of collaborators, including corrupt players within the private sector and government.

- Level 5: Buyers and consumers who are residents of foreign countries and generally lie beyond the reach of African law enforcement. These players control the delivery of the rhino horns into end-use markets and often foster corrupt relationships with government regulators to prevent disruption of the trade at ports of entry.

Pembient is confident that rhino horn consumers will prefer a legal synthetic product and plans to create “an unlimited supply” of its horns, pieces and powders. “One nice thing is that we’re competing against poaching syndicates, and these syndicates cannot really offer any legal proof of authenticity.”

In Vietnam, the company may be competing with a fairly established “cottage industry” which produces “rhino horn” from cow and water buffalo horns. The local manufacturing of imitations has had no measurable effect on curbing demand for the real thing. An estimated 90% of Vietnam’s retail rhino horn market is fake and well-known traders are said to have “months-long waiting lists” for real rhino horn.3

“Because it is appreciated that authentic rhino horns are very expensive, traders offering rhino horns for cheaper prices are often suspected of trying to sell imitation horns.”

There is no credible evidence to show that consumers of wildlife products would “switch” to a “synthetic” alternative. Meanwhile, the presence of lookalike products provides a convenient cover for wildlife criminals.

“The most promising way to reduce demand for ivory and rhino horn,” writes Dr. Ronald Orenstein, “is to convince buyers to stay away from all of it, not just to avoid the black-market supply, assuming they can tell the difference.”4

Ivory traffickers are notorious for using substitute materials. Grace Ge Gabriel, Asia Regional Director for International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), tells The Breakthrough Institute that smugglers use lookalike alternatives to cover illegally-sourced ivory.

“To reduce demand, we need to devalue ivory and stigmatize ivory consumption. Putting ivory lookalike products on the market reinforces the ‘necessity’ of having it. People who covet it to show off their wealth would want the genuine elephant ivory, and alternative materials would not be worth having for them.”

The International Rhino Foundation and Save the Rhino International agree that rhino horn consumption must be stigmatized, not encouraged. They opposed Pembient’s plan in a joint statement: “The availability of legal synthetic horn could normalize or remove the stigma of buying illegal real horn.”

An extensive study conducted by TRAFFIC (Trade Records Analysis of Flora and Fauna in Commerce) revealed that “new uses” for rhino horn in Vietnam are a key driver of escalating rhino poaching figures. Researchers identified four distinct rhino horn user segments.5

- Terminally or seriously ill patients: “Desperate individuals who are irrationally susceptible to notions of a panacea, especially if promoted by someone with authority like a traditional medicine doctor or encouraged by worried family members”;

- Affluent users on the social circuit: “Young, affluent habitual users of rhino horn are generally speaking, the most superficial, one could argue, mindless, consumers in Viet Nam, but probably account of the greatest volume of rhino horns consumed in the country today”;

- Affluent young mothers: There is a “strong demand for bona fide rhino horns and a sincere concern for procuring ‘real’ rhino horns, for self-medication purposes within the framework of traditional medicine”;

- Elite gift givers: “Many rhino horns are apparently purchased and offered as high-value, status-conferring gifts to important political officials and other socioeconomic elites within the country”.

Pembient insists it is not preying on terminally ill patients or worried mothers. “Obviously, most of the newfangled medicinal uses of rhinoceros horn (e.g., cancer cure) are pure quackery. The research on some of the more traditional uses (e.g., fever reducer) is less clear. We would definitely like to dispel people of the belief that rhino horn can cure cancer, and we’ll work to do so.”

Pembient has not addressed how it will convince cancer-stricken patients and desperate families that real rhino horn is “pure quackery” while simultaneously marketing synthetic rhino horn as a must-have ingredient in “nutritional supplements”.

Dr. Mark Jones, Programmes Manager, Wildlife Policy, Born Free Foundation, is skeptical of Pembient’s intentions.

“All over Africa and Asia, wildlife rangers, police officers and undercover investigators are risking their lives to protect rhinos. Then in comes an upstart, looking to make a name for itself, not to mention a pot of money, by encouraging new consumers to buy rhino horn.

“And what happens when these consumers want to graduate from synthetic rhino horn to the real stuff? Thanks, but no thanks,” says Dr. Jones.

To confound matters further, Pembient hopes to make it extremely expensive to test for differences between its product and real rhino horn. This will create unnecessary obstacles for investigators and law enforcement. Wildlife crime cases involving lookalike items might not receive desperately-needed attention, notes John Sellar.

“Bone, horn and Mammoth tusk items are often claimed to be elephant ivory and it may be difficult for untrained enforcement officers to tell the difference; a reason why some officials are reluctant to get involved.”

John Baker, managing director of WildAid, points out to Outside Online that Pembient has got it all wrong. “We’re trying to tell people that [buying rhino horn] is bad, it’s against the law, and that it’s illegal to transport rhino horn from one country to another. But Pembient is coming in and saying, ‘No, this rhino horn is OK.’”

There are international and domestic laws in place to protect endangered species, and it is critical that we support the work of those who are tasked with enforcement. Pembient is poised to create a nightmare for law enforcement officers at the coalface, particularly those in African and Asian countries with limited resources for tackling wildlife crime. The company’s distribution plan for its lab-grown horns will provide unlimited opportunities for wildlife traffickers to operate in “grey markets”, where lookalike contraband is mixed with legal “products”. In short, the manufacture and distribution of synthetic rhino horn is simply another wallet-fattening scheme to exploit the rhino crisis.

At the time of this writing, Pembient remains adamant about moving forward on its profit-seeking venture.

References (and suggested reading):

1. Sellar, J. (2014) The UN’s Lone Ranger: Combating International Wildlife Crime.

2. Milliken, T. (2014) Illegal Trade in Ivory and Rhino Horn: an Assessment Report to Improve Law Enforcement Under the Wildlife TRAPS Project. USAID and TRAFFIC.

3. Milliken, T. and Shaw, J. (2012). The South Africa – Viet Nam Rhino Horn Trade Nexus: A deadly combination of institutional lapses, corrupt wildlife industry professionals and Asian crime syndicates. TRAFFIC, Johannesburg, South Africa.

4. Orenstein, R. (2013) Ivory, Horn and Blood: Behind the Elephant and Rhinoceros Poaching Crisis..