By Glynis O’Hara, Conservation Action Trust

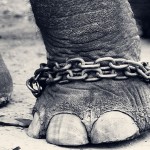

There will be no further culling of elephants in Kruger National park for population control.

So says Dr Sam Ferreira, SANParks’ large mammal ecologist. That’s because the new, “natural”, methods of managing them have severely curtailed the population growth rate, bringing it down to just 2%, from a high of 6,5% when culling was stopped in 1994.

Managing the effects of elephants is not about controlling populations. It is about letting natural processes influence where elephants spend time and what they do when they are in particular places.

Culling did not work for managing elephant impacts, admits the Kruger’s Elephant Management Plan, and the new method of imitating natural processes appears to be doing a much better job. Culling could, however, be used, in other scenarios, such as shooting a problem elephant, he said.

The current elephant population is estimated at around 16 900, said Dr Ferreira, based on the last count in 2012. It was 8 000 in 1994. However, without the new, more natural methods of control, the population would have been over 25 000 by now, if the 6,5% increase rate had continued at the time when culling stopped.

The new approach to manage the impacts that elephants have on various conservation values is a more ”natural” one, largely through limiting access to waterholes. Over two thirds of them were closed after 2003, starting in the drier, northern areas. As elephants moved away from newly closed boreholes, the landscape and vegetation got respite from elephant use.

Managing impact does not mean managing the numbers of a population – it’s now all about how elephants use the landscape and managing that. “Elephants need shade, water and food and prefer avoiding people,” said Dr Ferreira. “In the Kruger they used to have water within 5km of wherever they were and they had no reason to move around extensively.

“But now we’re restoring natural patterns. We’ve closed boreholes and we’re removing some dams, although that’s a much bigger operation. We’ve also dropped fences between ourselves and Mozambique in the north and private reserves in the west, allowing more spatial range.”

As expected, a typical natural process unfolded — with less easily available water, more calves and elderly elephants died and the birth rate went down. (The Kruger’s last major drought was in 1992/3, so the impact of fewer waterholes during drought is still to be seen.)

An elephant cow, pregnant for 22 months, could in the best circumstances have a calf every three years, said Dr Ferreira. But now, with the water restrictions, elephants are giving birth every 4.2 to 4.5 years. “It’s a classic population response.” Cows have to walk further to get to water and food and it takes its toll on body condition, hence reducing the rate of conception. Calves suckle up to three years when they start to get their tusks. After that, they have to walk to water and food, like the rest of the herd.

None of this means Kruger is littered with the bodies of dead calves, Dr Ferrreira hastens to explain. “One calf dying irregularly can set back a herd by four years,” he says.

The responses in the Kruger have been different in different areas. For example, in the north, survival rates have declined, while in the south (where there’s more natural water), the birth rate has declined. It’s not yet clear why that’s happening. “But basically, elephants are starting to look after themselves.” Natural regulation is taking place.

For the scientists, observing the impact of borehole closure and the changes in elephant reproduction rates takes time. “An elephant generation is 12 to 15 years and we have to monitor behaviour and impacts over the years.”

Now that more boreholes are closed, for example, elephants have moved to the rivers, accentuating impacts on vegetation there, and such “lag effects” have to be studied and managed. “We’ve identified 32 places where lag effects are happening, and we’re calling them ‘areas of concern’. One of the ways we have of addressing the issue is to mimic human presence as a deterrent.”

This could be done through various disturbance techniques, like noise (firing guns into the air for example), or small fires, using bee hives, or putting up a fence with chilli-pepper on it. The last has been experimented with at the Kruger’s nursery, where they used a cloth soaked in chilli pepper sauce. “Elephants just avoid it. But it only serves as temporary deterrent, they’re very clever and they’d eventually get used to it. As for the bees, the thing is that they have to survive long, dry seasons too.” There have been experiments with beehive sounds, but again, the elephants would work it out after a while. “It would need a reinforcement technique,” says Dr Ferreira.

Tourists have to be considered too. The main north-south road “historically was a military road and there weren’t that many places to see animals, so they put in boreholes to bring the animals to the tourists. Now we want to take the tourists to the natural water areas, through loops off the main road.” But creating new infrastructure takes time, the Kruger Park Elephant Management Plan acknowledges, adding that some artificial water may have to be maintained to manage visitors’ expectations.

Tourists have also always enjoyed the historic big trees at the rivers and preserving them is a concern for the park. One way to keep elephants away is by packing large, sharp rocks around them.

The data on vegetation effects is not conclusive in the Elephant Plan, published in 2012. “Limiting elephants did not prevent a decline in the structural diversity of the woody vegetation of Kruger,” it says. In fact, “vegetation diversity increased with high elephant density in certain regions of Kruger”. So it’s an area that needs a lot more study and understanding.

One of the complexities is that the highest rates of damage are not necessarily where the highest densities of elephants are. The impact is not necessarily related to numbers, and this, it turns out, may be all about the boys. Elephant bulls take a very long time to mature, producing viable sperm at about 15, going into intensive musth cycles at about 30 and really becoming competitive at 40- to 45 years of age, said Dr Ferreira. “So teenage boys may get very frustrated and thrash trees. And therefore the kind of elephants we have in a particular spot is important.”

As far as human-elephant conflict goes, in South Africa, there’s been a relatively low number of incidents with villagers on the edge of the park, says Dr Ferreira.

“I have yet to see the fence that will keep an elephant in all the time. We’ve collared about 150 elephants and only one of them has never left the park.” Mostly they moved into private reserves and into Mozambique.

“Most elephants will move out of the park at night when the marula tree starts fruiting, eat the fruit and come back, avoiding humans. But the elephants flatten the fence and buffalo can then get out and they can carry disease and contaminate domestic stock. So what’s the solution? One idea is to build a lower fence that elephants can step over but that keep the buffalo inside the park.”

The main problems for villagers, he said, were actually drought, disease, and wild animals like rodents, baboons and monkeys. The Management Plan also mentions predators. Elephant conflict is actually rare. Legislation does however, allow a provincial authority to shoot a “damage causing animal” once it’s outside the Park.

In effect, this is a giant experiment, to see how all the Kruger’s animals, including the elephants, adapt to the changes. So far, so good. And if we never need to repeat awful scenes of herds of elephants being gunned down from helicopters, the scientists deserve a medal.

Elephant poaching in Kruger

Just two elephants had been poached in the north of the park this year, said Major- General John Jooste, Commanding Officer of Special Projects at Kruger.

Elephant poaching is not a crisis in South Africa as yet, unlike in East Africa (where 12 000 are estimated to die annually), said Dr Ferreira. “We’re probably also in a better position to deal with it, because we have anti-rhino poaching forces in place already,” said Dr Ferreira.

There are some logistical problems for would-be poachers, Dr Ferreira explained. After shooting an elephant, it takes some time to cut out a tusk. “Then you have to hack off the head to get at the other tusk. So the poachers spend a much longer time at the locality than with rhinos.” And the longer the poachers take, the more likely they’ll be caught, given that there are anti-poaching units patrolling the park.

The Kruger’s Elephant Management Plan

The focus for Kruger Park is on natural population and spatial use management and a tolerance of nature in constant flux.

Other parks with elephants are including contraception in their plans, but not Kruger at this stage.

The plan focuses on maintaining, or restoring, ecosystem integrity; providing benefits to people; and taking cognisance of aesthetic and wilderness qualities.

Five key objectives, often overlapping, cover areas such as managing elephant ecological impact, damage-causing elephants, anti-poaching (“low” incidence at the time of the report), aligning plans and policies with adjoining parks and stakeholders, including Transfrontier Conservation Areas, and monitoring and research.

“Adaptive elephant management” includes a complex table of options for the different regions, with “lethal shooting” as an option for human- elephant conflict as well as for vegetation loss and loss of large trees.

Culling is accepted in the government’s Elephant Norms and Standards policy of 2008 as an option of “last resort” only that has to conform to “strict conditions”. A “culling plan” has to be prepared with an ecologist and approved by “the relevant issuing authority”.

The plan notes that six people were killed by elephants between 2000 and 2005 (5 villagers and one ranger), although it does not say where this was. In the same period, 75 elephants associated with fence breakage and damage to property were killed by the Limpopo Department of Environmental Affairs, while the Mpumalanga Department “killed an unknown number” south of Olifants in recent years, it says.

About the author: Glynis O’Hara lives in Cape Town and is a former editorial director for Media24 Africa, overseeing five publications in Kenya, Nigeria and Angola, as well as a former editor of Femina and The Big Issue. Now freelancing as a writer and consulting editor, she won a Mondi runner-up award for a feature in 2003 and won seven awards for Femina magazine in just two years, from 2007 to 2009. After many years of helping people fix up their copy, bring passion to picture editing, effectively combine meaning and design and solve crises, she’s returned to the craft of writing. Anything to do with nature, the wild, conservation and the planet floats her boat. Glynis works with Conservation Action Trust www.conservationaction.co.za.