In July 2013, South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs released its “Rhino Issue Management” report, a 46-page attempt at making the case for trading in rhino horns. The document has since received an unflinchingly candid review by former Chief of Enforcement for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), John M. Sellar.

We are delighted that Mr. Sellar has kindly given us permission to reprint his thought-provoking commentary below.

Is there a Plan B for rhinos?

by John M. Sellar

I sincerely hope so, because the recently-published Plan A contains some significant mistakes, naivety and apparently wasn’t proof-read sufficiently.

I really had not intended returning to this matter again but, at the risk of being boring, I feel driven to comment on a document that South Africa’s Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) has made public and which is being widely quoted by the media. The ‘ Rhino Issues Management (RIM) Report 2013′ makes for interesting reading and it attempts to pull together views collected during an intensive consultation exercise.

It contains some lengthy recommendations, addressing a range of issues. Its authors, and I don’t intend them any personal criticism as they’d been set a very difficult task, have tried to find ways in which the current rhino poaching crisis might be tackled, drawing conclusions from what they acknowledge were diverse opinions. However, if effective answers are to be identified, and ways-forward chosen, then decision-makers risk being misled by a report that reads well but is flawed.

Maybe what the public are seeing is some cut-down version of a much larger document but I struggle to find distinct explanations within the main text for several of the important recommendations. For instance, the Minister is called upon to establish a “Global Rhino Fund” to which national and international donors will be encouraged to contribute. There are multiple suggestions as to how those monies will be used.

The word ‘global’ means, to me at least, worldwide. There are many populations of rhinos in different African and Asian countries but the species cannot be found across the whole globe. Several of the remaining populations are considerably closer to extinction than those of South Africa. So, one might understand that the proposed Global Rhino Fund is intended to help all rhinos. But there’s nothing in the text to confirm such an interpretation. Instead, it seems ‘global’ should perhaps be ignored and that the authors actually want the world to contribute to saving only South Africa’s specimens of the species.

There’s nothing wrong with proposing such an appeal but at least make clear what is intended. Oh, and by the way, get ready for the other countries with rhinos in their territories to ask for help too and to question why South Africa needs assistance more than they do.

Not surprisingly, another recommendation calls for strengthening anti-poaching work in various ways. Highly commendable. Gets my vote every time. But an “Impact” that is predicted as a result of this recommendation makes for fascinating reading – “Crack Rhino Rangers, properly resourced, will instil fear in the poachers”. Just where did the authors come up with evidence to justify that conclusion? How many poachers have been shot dead or wounded in South Africa in recent years? They all felt the impact of a bullet but what’s the overall deterrent effect been? Yes, beef up rhino protection but don’t promise outcomes that are just plain silly. I’d be willing to bet that many of the poachers who are currently crossing borders into national parks and protected areas come close enough to soiling themselves already whenever they hear a patrol approaching. Although the report mentions the need to address what is driving these people to risk death or injury, it doesn’t give enough attention to the issue.

Oh, and by the way, maybe you guys who are patrolling Kruger at the moment should go back to barracks. Seems you’re currently not crack enough.

Judging by media reports, the DEA maybe finds some of the recommendations troubling too. It appears, for example, to baulk at the suggestion that every rhino in the country should be de-horned. I get the impression that the recommendation itself isn’t necessarily unacceptable but I suspect the cost and time involved would probably frighten off any government agency. Little wonder, as the report estimates that de-horning 10,000 rhinos would cost 84 million Rand and would take over 1,000 days. It is puzzling why an estimate for 10,000 animals is quoted, when the report indicates that there are over 20,000 rhinos in the country. So, we are actually talking about 168 million for an exercise that would take almost five and a half years to complete. For those of you who, like me, aren’t used to thinking in Rands, that is over 16 million US dollars, 11 million British Pounds or 12 million Euros. I hope the Global Rhino Fund attracts a lot of donors.

Oh, and by the way, the de-horning needs to be repeated every two to three years. Shame, as that means you’ll have to start all over again before you’ve even finished the first de-horning.

Not a recommendation, but given some focus and left hanging as if perhaps an alternative, is the notion of chemically treating or poisoning rhino horns. The idea here is to deter humans from ingesting horn or poachers from harvesting doctored horns.

Every year hundreds of drug users die after taking narcotics that have been adulterated or are of poor quality. The risks associated with drug misuse are well-known but don’t appear to deter devotees. It is for sure that drug dealers, and their organized crime controllers, couldn’t care less if customers are killed from time to time. Why should rhino horn traders? There seem few grounds to believe that cancer sufferers, convinced that rhino horn will cure them and just as driven as any heroin addict, will be put off by warnings of chemically-treated horns.

I was intrigued by the report’s reference to Botox as a toxin that might be used to protect horns. I don’t know about South Africa, but Botox is best known in the UK for various cosmetic procedures, designed to remove wrinkles and lines, so that you look younger and more attractive. Please don’t give organized crime any ideas for further uses for rhino horn, as they might find Botox-laced horns as being commercially appealing. I’m only half-joking; the report suggests that it is the current ban on trade that has led to increased poaching. No it isn’t. It is the recent emergence of new forms of demand for rhino horn, some of which are wholly bizarre, perhaps fashionable in nature and, consequently, risk being some time-limited fad. (That’s another aspect the report doesn’t take account of.)

The report says that threats from pseudo-hunting (persons posing as big game hunters in order to acquire horns as trophies, but intending to launder them into illicit markets) “have largely reduced”. Stories of a 16-person gang in the Czech Republic being busted last month for just such activities would seem to contradict that claim.

The major issue the report tackles, at length, is legalizing trade in rhino horn and commercializing the keeping of rhinos. Of course it does, and perfectly appropriately too. Now, at this point let me express again my relative indifference to whether trade in rhino horn occurs or not. But there are several issues that don’t seem to be fully considered or understood by the document’s writers.

The report acknowledges that one needs to identify potential trading partners. (There is absolutely no point in South Africa designing trade regimes unless some importing country has declared itself ready to engage in commerce.) The report names China, Malaysia and Viet Nam. China is understandable, as it has centuries-long medicinal use of rhino horn. Viet Nam makes sense, too, as it is where the current belief in rhino-horn-cancer-cure emerged. But Malaysia? Where did that come from? The report states that these countries were options suggested by stakeholders. Based on what? I hope it wasn’t racial stereotyping. Have any of those countries indicated they are ready to collaborate? This aspect is almost mentioned in passing yet it will determine absolutely whether anything that is suggested subsequently can take place or not. Much, much more emphasis needs to be placed upon this.

In its reflections upon trade in animals and their products, the report makes more than one reference to commerce in ivory. It seeks to reassure possible critics or sceptics that trade in horn won’t involve killing rhinos. By way of comparison, it states “Elephant ivory cannot be harvested without killing the elephant”. Really? Since when? This statement is utterly astounding. It flies in the face of everything that South Africa, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe have told the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), and the international community, in recent years. If the remark is accurate and endorsed by DEA, it implies the ivory stocks that were previously sold, and declared as primarily resulting from natural mortality, were actually obtained through deliberate culling. I think we can safely assume this comment was a mistake, but what a glaring one to find in a government publication.

All of the above aside, and ignoring other inaccuracies in the document, my main concern with this report is how its authors apparently believe agreement to proposed legal trade might be acquired and, especially, how quickly. The RIM report acknowledges that international trade in rhino horn must be authorized by CITES. It also acknowledges that such agreement, ordinarily, could not be achieved until the next major CITES conference, which will be in South Africa in 2016. The authors recognize that South Africa’s rhinos cannot wait that long. (Assuming that trade will be an effective response.) They suggest that an “interim application” be made in terms of Article 27 of the Convention. Just one problem here. There is no Article 27 in CITES.

Article XV, which is presumably what the report authors had in mind, does indeed provide for an interim procedure. It offers the opportunity for decisions on species-specific trade regulation to be determined by a postal vote. Although this process has been used in the distant past, I cannot remember any example in the last almost two decades. The likelihood of the process being used successfully for anything contentious is, in my opinion, highly remote. Which brings me to my final observation. The report doesn’t make nearly clear enough how contentious a rhino trade proposal is likely to be for many governments both inside and outside Africa. There appears to be no contingency for a trade proposal being rejected, either in 2016 or before.

I do not believe that implementation of Plan A anytime soon is feasible, regardless of whether one addresses its flaws.

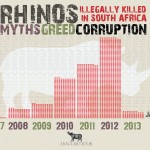

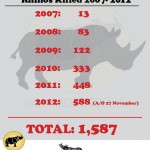

The DEA announced last month that 515 rhinos had been killed this year. It seems reasonable to predict that more animals will be poached by the end of 2013, and maybe more even than the appalling total of 668 in 2012.

So, is there a Plan B?

(Editor’s note: The “Rhino Issue Management” report can be downloaded here.)